Many people reduce animals to their instincts. However, recent research indicates that animals make conscious decisions, shape their environment, and influence their social relationships. Animals particularly demonstrate their abilities when they resist human violence. Activist and author Sarat Colling has written a book on this subject titled «Animal Resistance in the Global Capitalist Era». Tobias Sennhauser (TIF) spoke with her about it.

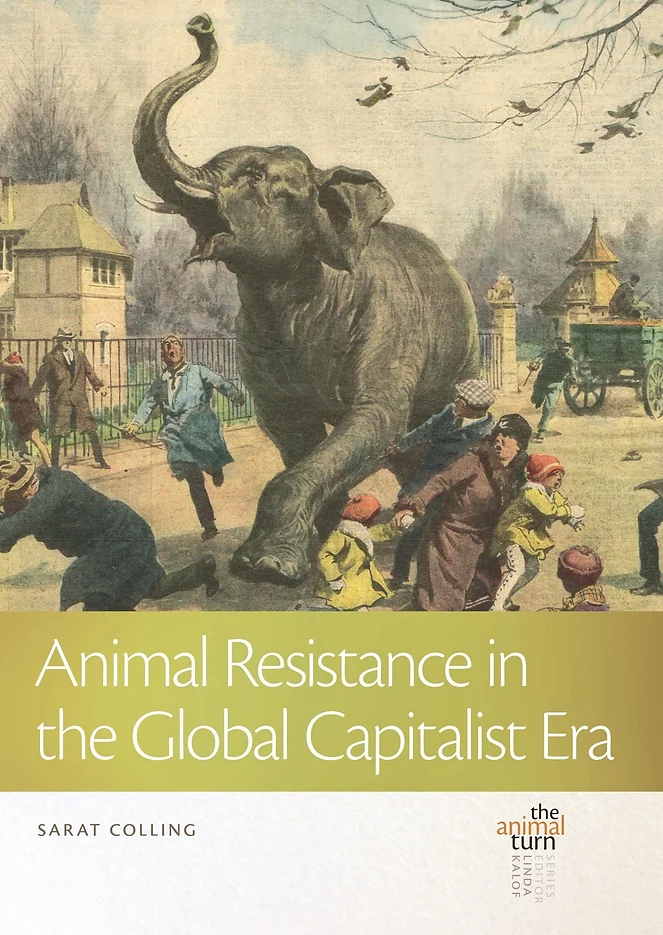

TOBIAS SENNHAUSER: The cover of your book features an elephant escaping in Basel. What happened there?

SARAT COLLING: The elephant made a bid for freedom, breaking free from their enclosure at the Basel Zoological Garden. With workers in pursuit, the elephant sought refuge in a nearby garden but was recaptured soon afterwards.

Your book is about „animal resistance.“ What do you mean by that?

Animal resistance is when nonhuman animals struggle for autonomy against human oppression—a rejection of conditions such as exploitation, captivity, and dispossession. Animals have resisted for as long as human consumerism and politics have disrupted their lives through institutionalized violence or widespread habitat destruction. This resistance may entail escape, retaliation, liberation of kin, and everyday defiance.

Please share some examples.

Yes, there are so many stories once we start looking. After enduring years of cruelty in the circus, an elephant named Tyke escaped through city streets and was tragically shot 86 times. The sperm whale Mocha Dick rammed a whaling ship to avenge the death of his kin and save the surviving whales. Mountain gorillas of the Kuryama group have learned to dismantle dangerous snares and warn others to avoid them. Through their resistance, these individuals influence social and political realms, bringing attention to the plight of animals in our society.

How does the public react to animal resistance?

To maintain the status quo, the animal industrial complex goes into damage control. Owners downplay animal resistance, describing it as a rare anomaly or accident. This minimization is to deflect scrutiny from the harsh realities of animal exploitation. It’s part of a broader effort—of distancing strategies—to dissociate animal products from their production.

Animals repeatedly make their escape in Switzerland too, such as in Oensingen or Seewen. The media apparently enjoys reporting on these incidents.

Indeed. Distancing strategies also function through the media, which celebrates animals who escape, for instance, as uniquely exceptional, having “earned” their freedom. This narrative perpetuates selective empathy while failing to acknowledge the horrors that have forced these animals to flee.

Yet, stories of the animals who resist inspire contemplation and interrupt distancing strategies. In a world where billions of animals are killed each year for human consumption, those who resist may be recognized as individuals.

And how do the people react?

Public reactions are mixed, from empathy to cognitive dissonance or selective compassion. Take the case of a cow in Montana who, in 2006, leapt to freedom and swam across the Missouri River. Named the Unsinkable Molly B, her story ended happily with sanctuary, thanks to widespread media attention and public support.

What is lesser known is that on the same day as Molly B’s escape, several sheep fled from the very same packing plant. Yet, upon recapture, they were slaughtered without public outcry. This disparity highlights an inherent contradiction: many who celebrate animal resisters’ freedom simultaneously prop up the system by consuming other animals who are unseen and unheard. The reality is that while it’s easy to grant escaped animals special status, they would all escape if they could.

What happens to animals that successfully escape?

For example, they find a place at sanctuaries, where communities of various species emerge and traumas can heal. In addition to caring for the animals, these sanctuaries play a crucial role in addressing animal resistance by providing a haven for those who have escaped or been liberated from exploitation. They serve as spaces of refuge, fostering a just multispecies community. While providing essential care, sanctuaries also educate the public about the exploitative systems that necessitate the animals’ resistance.

Sanctuary residents are active participants in their communities, teaching, parenting, and caring for one another. For example, a cow named Justice adopted the role of welcoming new residents at Peaceful Prairie Animal Sanctuary. After escaping a slaughterhouse truck, Justice had been distraught, but the empathy he received from a steer named Sherman—who licked him through a fence when he arrived at the sanctuary—showed him he was safe. As his caretaker Michele describes, Justice remembered this kindness and took it upon himself to comfort new arrivals.

Animal resistance has entered pop culture with movies like Chicken Run (2000). Isn’t there also the risk of anthropomorphizing animals?

Humans have a tendency to represent themselves through depictions of other animals. This occurs across various contexts. On the other hand, a film like the Plague Dogs (1982) offers a more realistic portrayal of animal resistance, where dogs behave as dogs.

Much of what has historically been termed anthropomorphic will one day be supported by scientific research. Marc Bekoff has a compelling concept of “biocentric anthropomorphism,” which suggests we should interpret animal behavior from the animals’ perspective, acknowledging their social structures and moral behaviors as forms of justice and empathy unique to their species.

It is important to represent the unique lived realities of animals, while recognizing them as agents of social change. Yet even the more fantastical depictions of animal resistance reflect to some degree an evolving understanding of animals’ lives that challenge conventional views.

How should animal rights organizations respond to animal resistance?

Animal resistance must be taken seriously in the fight for collective liberation. Animal rights organizations can act in solidarity, mobilizing strategically on their behalf. They can build campaigns and activism around the resistance. When animals break free, they can galvanize public support by protesting at the site of escape. Social media campaigns can demand immediate action to secure animals’ release to sanctuaries, and mail bomb those with a say in their future. This advocacy will keep the individual in the public eye, so they are not consumed back into the system.

What can such a protest achieve?

Let’s take the example of the aforementioned Tyke again. She endured captivity in circuses after being abducted from Mozambique in 1973. Strong-willed, she repeatedly resisted her trainers‘ commands, despite knowing that severe punishment would follow. Her tragic plight became widely known in August 1994. During a performance in Honolulu, she fought back and fled through the city streets. Police cornered Tyke and killed her with nearly 100 gunshots. Her tragic final moments were broadcast internationally, sparking debates, protests, and legal challenges against the use of animals in circuses. In the years following, more than 20 countries and over 300 cities and regions banned using wild animals in circuses. Lawsuits were filed against the circus as well as the City of Honolulu and the State of Hawaii. In 2004, the circus owner was charged with multiple animal welfare violations, leading to a fine and the seizure of elephants. Tyke became the catalyst for the establishment of The Elephant Sanctuary in Tennessee, a 2,700-acre haven, where six of these elephants found refuge.

Tyke should have been one of those to finally feel the grass beneath her feet. But her struggle was not in vain. Through her resistance, Tyke made visible the struggle of elephants used for entertainment and became a powerful symbol for animal liberation. By acting in solidarity with resisters like Tyke, we spark a multispecies social justice dialogue that can lead to tangible changes in the lives of animals. Animals are on the front lines of their social justice movement.

What would need to change in our society so that animals would no longer need to resist?

We must dismantle the structures that uphold animal subjugation. This includes dissolving human exceptionalism and capitalist logics that render animals property and commodities.

We must radically reimagine our relationships with other animals. A powerful example takes place in Switzerland, where Sarah Heiligtag and her team is transforming agriculture. In 2013, they acquired a farm in Hinteregg and turned it into a vegan farm and sanctuary. Since then, through their “Transfarmation” initiative, they have helped over a hundred farmers transition to plant-based, sustainable agriculture.

Animal agriculture must be replaced by forests, sanctuaries, gardens, and open land, and animals should be rewilded. By showing solidarity with animals in resistance, we create a just world for all.

About Sarat Colling

Sarat Colling is an activist and writer. She is particularly interested in stories about animal agency. Her books, such as Animal Resistance in the Global Capitalist Era and Chickpea Runs Away, tell stories of animals in resistance. Her upcoming book also focuses on this theme, featuring over 50 stories of animal defiance illustrated by vegan artists. Proceeds will support the animal sanctuary movement. Sarat Colling lives on Hornby Island, BC, in Canada in a self-built tiny house with her chihuahua Xena.

Der Beitrag Interview Sarat Colling EN erschien zuerst auf Tier im Fokus (TIF).

Meist kommentiert